As Greece stares into the abyss, Europe must choose

The way out of the financial crisis faced by Greeks requires a choice about what kind of Europe we want

Six inches from the riot policeman's shield outside the Greek parliament last Friday, a tall, pale boy was shouting at a man who could have been his uncle: "It's your generation that brought us to this point, but it's mine that has to pay for it. You have to take responsibility for what's happening here." Across the road, a middle-aged woman roared at the line of cops: "Traitors! Collaborators! We're Greeks. You're beating up your mothers and your sisters." Another, her head wrapped in a pink scarf, screamed at the parliament: "They've drunk our blood, we don't have anything to eat. They've sold us to the Germans. My child owes money, they're about to take her house. I hope they all get cancer." All of them were in an ecstasy of rage, reluctant to go home and lose that temporary release.

As I write, the Greek parliament is preparing to vote on the bond swap agreed with the country's private creditors and on the new deal with the EU and the IMF, which would lend the country €130bn in exchange for cuts that slice the last little bits of flesh from the economy – including a 22% reduction in the minimum wage and 150,000 public sector job losses by 2016. Without the deal, Greece will default by March; with it, the country will sink into a still deeper depression, with no end in sight. In a televised effort to rally the country behind yet more austerity, the finance minister, Evangelos Venizelos, laid out a blunt choice between sacrifices and worse sacrifices, humiliation and still deeper humiliation, if Greece should default and leave the eurozone.

It's not clear, though, how many people were listening. Exhausted by interminable cliffhangers and last chances, many Greeks have turned off the terrorist soap opera of the TV news and are trying as best they can to get on with their lives. The misery to which Athenians have been reduced – the soup kitchens, the homelessness, the depression and suicides, the rising tide of poverty that's swallowing the middle class – is now a staple of the features pages. It's harder to describe the sense of pervasive breakdown that gets under the skin; the feeling of disorientation and lost identity that comes with the collapse of the assumptions people lived by and the stories they told themselves about the future and the past.

When you ask people on the street if they would rather Greece went bankrupt than submit to further measures, many now point out that it is already bankrupt, that public sector workers have gone unpaid for months, that hospitals have no supplies, that the poor are being wrung dry in order to pay the banks. "Let's get it over with," a woman who works for the education ministry said to me. "Then we'd know we only had €250 a month and we could start again. This is not the people's Europe we dreamed of." The fact that Poul Thomsen of the IMF, the eurozone's poster boy Mario Monti, the markets and countless economists agree that more austerity will deepen Greece's depression without making the debt sustainable adds weight to her argument. The icy reception given last week to the Greek delegation in Brussels confirms the sense that its lenders are ready to end the relationship.

Why, then, have large sections of the Greek elite clung so hard to the fantasy that a new loan deal can "save" the country? The obvious answer is that default is a black hole and an enormous risk. No one can predict what suffering a default might bring. Another is that the current crop of politicians built their careers in the system that is now unravelling, based on oligarchies, clientelism and corruption; they've proved unwilling to make the reforms that might, in a different global climate, have revived both Greece's economy and its democracy.

The deeper reasons, though, may be cultural and political. The crisis has intensified old splits in Greek society. You can see it in the polls, which show support ebbing from the centre to the edges of the political spectrum, and especially to the fragmented left. You can see it, too, in the historical parallels people reach for in a vain attempt to name this unprecedented nightmare. Protesters chant slogans from the dictatorship of 1967 to 1974, comparing the deal's Greek enforcers with the CIA-backed junta. Both left and right talk about a new German occupation – an understandable reference given that Germany is calling the shots and that Greeks last queued at soup kitchens in the 1940s, but one that can edge into racism or crude exaggeration, as in a recent headline that read simply "Dachau". Both those tropes call up the silent ghosts of the Greek civil war, which launched the cold war in Europe and outlawed the Greek left for the next 30 years. In this story, the west plays the part of the repressive imperial interloper.

For the liberal centre, this is populist anathema. To them Europe is still Greece's heartland and its hope, the only guarantor of liberal capitalism, human rights and democracy. A few weeks ago a distinguished law professor compared the prospect of default to the Asia Minor disaster of 1922, which brought a million-and-a-half refugees into Greece and convulsed the state, and went so far as to suggest that leaving the eurozone would end the 200-year cycle of the Greek Enlightenment.

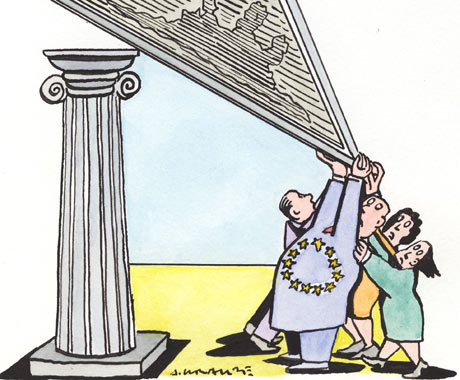

The trouble with historical metaphors is that they can obscure the present: what's really at stake here is not Greece's identity but Europe's. All eyes are fixed on Athens, but the way out of the crisis requires a choice about what kind of Europe we want. The one we have now, with its deep structural inequalities and its rigid adherence to a failed economic ideology, protects neither democracy nor human rights. Stiff-necked and punitive, it prefers to eat its children.

No comments:

Post a Comment